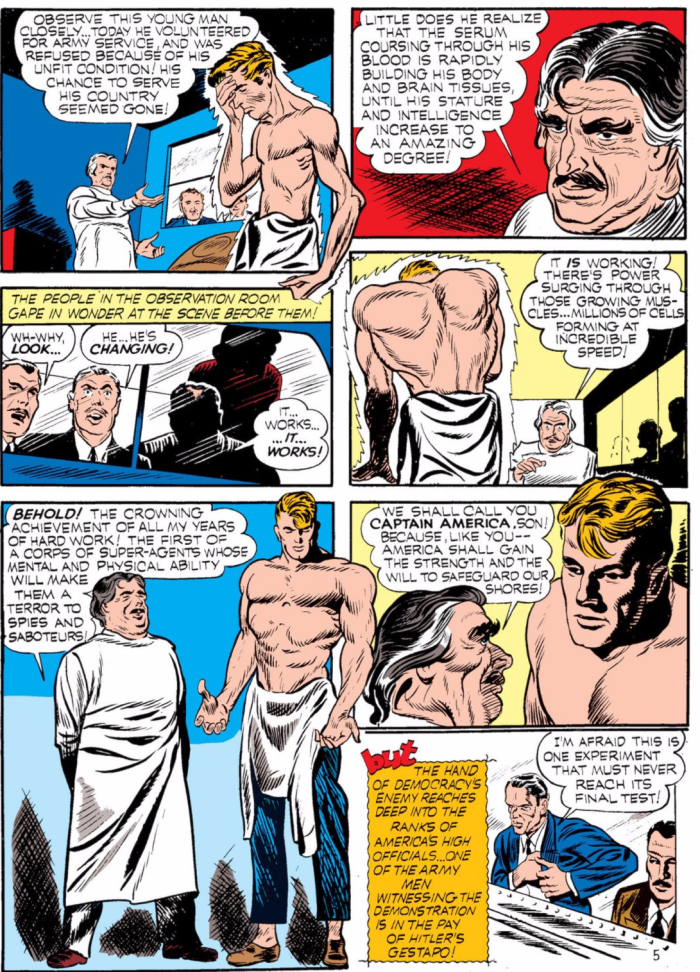

Superheroes and secret identities. They go hand in hand. Most superheroes have secret identities that allow them to have lives outside of saving the lives of everyone else, but mainly it’s to give them privacy and protect their loved ones from the awful intents of their villainous counterparts. However, it also means that they can take of the mask and disappear when it comes time to answer for destroying things around the city. So, I pose another question: Should superheroes have to fight crime without a mask?

Who had to clean up the buildings and light posts of web fluid after Spider-Man is done patrolling the city? Who had to rebuild an entire city after Superman destroyed building after building when Zodd came to Earth? Who had to reconstruct an entire infrastructure after the Avengers episode in New York City? The answer to all three of these questions is: the people. The taxpayers are tasked with righting the wrongs of these superheroes when they go about “saving” them, so should they be allowed to hide after they’ve finished rescuing everyone? Are they really helping anyone when they’re totaling cities in the process?

But wait, before you answer that… What would have happened to the people of Metropolis if Zodd would not have been stopped? And who really wants to know what would have happened to New York, if not the entire planet, if the Avengers hadn’t fought off those aliens? Superheroes save people. That’s what they do. Unfortunately, it means that they have to blow some stuff up, crash through some places, or break some things. Often times, the heroes don’t even have time to finish saying “You’re welcome” before they’re crucified for the wreckage they’ve caused. But if they did it because they were trying to save people, is it not okay?

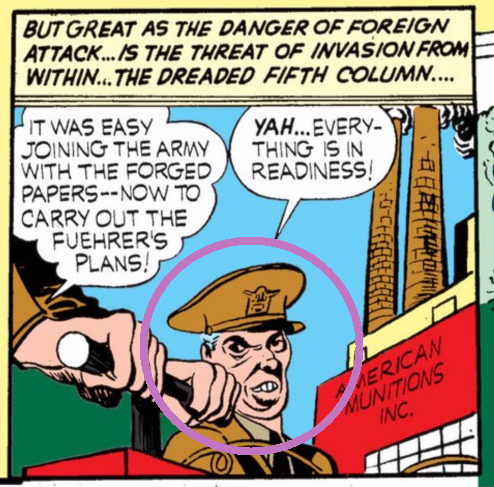

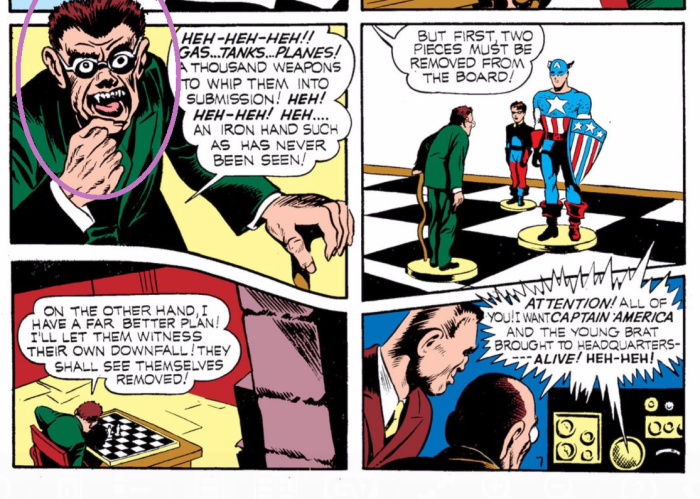

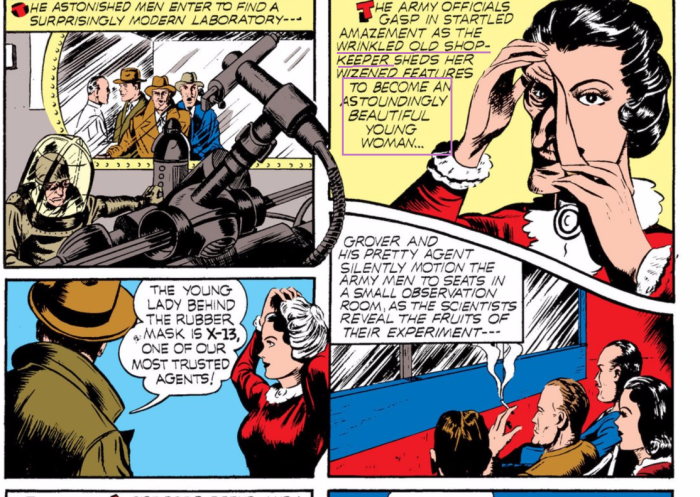

So I leave the question to you, the people. In the spirit of Captain America: Civil War coming soon to a theatre near you, I ask: What do you think? Should superheroes have to fight with their identities known, so we know who to blame? Or should we just say thanks, and keep it moving?